Senglea is the smallest but most densely populated of Cottonera’s towns. Situated on a promontory of 823 metres in length that is 320 metres at its widest point, Senglea is almost entirely surrounded by sea. It is for this reason that the town is also popularly known as l-Isla, a name derived from isola – the Italian word for ‘island’. Two mounds at the neck of the peninsula attach it to the mainland. These are known as St Julian’s Hill, and Mill Hill – the site of one of Malta’s first windmills.

|

|

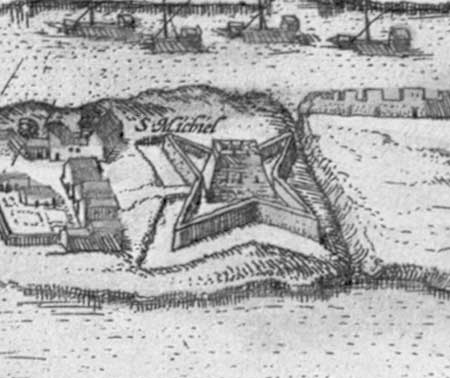

Fort St. Michael in the 1550s

|

Up until the early 14th Century the peninsula was mere wasteland and practically uninhabited. The first structure to be constructed on it was a chapel dedicated to St Julian in 1311. This was renovated in 1539, redesigned in 1696, and finally completed in 1711 when the Bishop proclaimed St Julian as Senglea’s Patron Saint. Following the building of this chapel, the peninsula came also to be known as St Julian’s Hill. The chapel was last restored after World War II.

By the arrival of the Order in 1530 l-Isla was a small fishing village with little more than three hundred houses in which about four hundred inhabitants resided. Grandmaster L’Isle Adam (1530-36) had no plans for l-Isla’s defence and, attracted by the peninsula’s potential as a site for hunting and leisure, L’Isle Adam was quick to embellish the peninsula by planting a good number of olive trees and adding a second windmill. Both of these windmills are clearly depicted in D’Aleccio’s paintings. L’Isle Adam also built his second Magisterial Palace on St Julian’s Hill. There he could relax while hunting along with his closest aides.

|

|

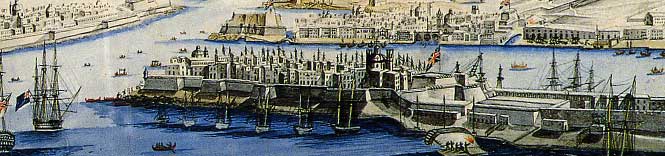

Senglea under Turkish attack in 1565

|

Since the Magisterial Palace was built over a large cave that featured a sculptured mermaid on its ceiling, the palace was named Villa Sirena. During the summer months, boats sheltered in the cave and the garden was surrounded by a pergola that supported a canopy which was overflowed with vines. In 1590 the Order passed this palace to the Knight Vincenzo Caraffa, a relative of Grandmaster Carafa (1680-90). From records dated 19th August 1882, it appears that by then the Villa had become known as Villa Davies and was used as a venue for theatrical performances – thus retaining its original function as a haven for leisurely pursuits.

Grandmaster Juan d’Homedes (1536-1553) also wanted his own villa on the peninsula, and so another Magisterial Palace was constructed to the highest specifications. Employing an extensive body of servants to tend his private garden which also contained a world famous menagerie, Grandmaster d’Homedes lived a life of luxury while the surrounding peasants were dying of hunger. This ensured that d’Homedes was by no means a popular grandmaster. During the years, the palace was leased to private interests. It is held that in the mid 19th Century, one of these lessees, Karlo Mamo, while dismantling d’Homedes’s double-walled bedroom found a decorated casket containing only a small pair of scissors. This was interpreted to be intended as a pun for chatter-boxes and gossipers to cut off their tongues.

|

|

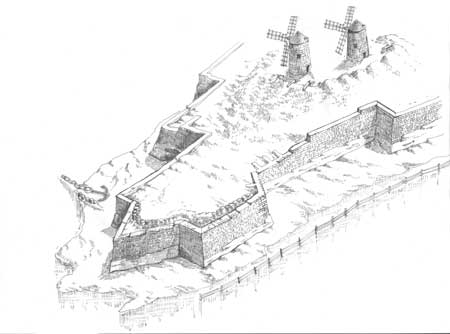

Fort St. Micheal in the early 20th centuary prior to its demolition in 1921

|

After the 1551 ransacking of Gozo, when about 6000 Gozitans were enslaved by the Turks, d’Homedes became aware of l-Isla’s vulnerability to an attack from the other side of Galley Creek. Fearing another raid in the following year, d’Homedes initiated a fortification programme for the peninsula in 1552. Chevalier Pedro Pardo was commissioned to build Fort St Michael at the neck of the peninsula on the Monte del Molino, or St. Julian’s Point, from where it could dominate l-Isla’s entrance from the landward side, command all movements on the peninsula, and protect the nearby Borgo from a South-Western assault. D’Homedes inaugurated the fort – a large, square and low tower topped with a battery – on the 8th May 1553. The construction of this fort was financed by a tax levied on the local population who strongly objected the Order’s legitimacy to tax them.

Claude de La Sengle (1553-57) continued in d’Homedes’s footsteps. Immediately after taking office in 1553, La Sengle commissioned military engineer Nicola Bellavanti to build a curtain along French Creek and a strong bastion at Isola Point. By 1554 Sheer Bastion sealed off l-Isla from the mainland village of Burmula, and by 1557 a bastioned enceinte encompassed Fort St Michael. Pressed for time, fortification works proceeded day and night on a shift basis, as bastions were constructed out of rock cut from the nearby ditches. The progress made soon started to shape the promontory into a

|

|

Senglea Point known as The Spur, a reconstruction of defences at the time of the great seige

|

new fortified town – prompting La Sengle to raise its status to that of a city bearing his own name. From then on, L-Isla was also known as Citta La Sengle, or Senglea.

The land-front fortifications coupled with the bastioned enceintes all along French Creek on the Western side, and Kalkara Creek on the Eastern side – even though not completely finished by the Great Siege of 1565 – created a compact block of fortification. These not only shielded Citta Nuova and Citta La Sengle from their land-front and lateral sides, but more importantly still, they also extended greater security to the Order’s naval squadron which was berthed in Galley Creek. The importance that the Order attached to the security of Galley Creek and its galleys is evidenced by the importation of a 300 pace-long iron chain from Venice in 1554. This was utilised to seal off Galley Creek in times of crises when it was stretched between St Angelo and Isla point – where a chain store and a capstan were built. The chain required a whole day’s work to put in place, and was supported all along by wooden barges. The huge iron collar of one of the anchors of the Carrack was used to keep it in place and once set up – it was guarded day and night. It is also believed that another chain was imported in 1563 to be stretched between St Elmo and Gallows Point. By 1778 however, the use of such a defence had apparently been discontinued, as when Napoleon appeared off the Maltese coast, the chain could not be found and Galley Creek had to be sealed off by means of strong cordage.

|

|

Plan of Senglea and Birgu

(after D'Aleccio)

|

Within the walled city of Senglea, La Sengle also built the Palaces of the Galley Captains so as to have them closer to their galleys which would have been moored on the Senglea side of Galley Creek. La Sengle even went further into the urbanisation of Senglea when he felled the trees that had been previously planted by L’Isle Adam in order to provide more space for accommodation purposes. In contrast with Birgu, where all streets converge to the main square, La Sengle saw that Senglea’s street planning conformed to the logical and more attractive urban design of a mathematically ordered grid layout. He persuaded people to move to Senglea by offering them land and houses at nominal prices as incentives. By this, he managed not only to populate the new city in a relatively short time, but he also relieved the congestion in Birgu.

During the 1565 siege, Fort St Michael was ably manned by the Italian Knights, while Senglea’s western flank was heavily battered from Corradino Hills by the Turks who pounded the fortifications for two months with marble shot. In fact, Senglea nearly succumbed to the invaders and would surely have done so had it not been for the wooden pontoon bridge that linked it with Citta Nuova. This enabled extra arms or reinforcements to be supplied whenever and as the tactical situation so dictated.