|

|

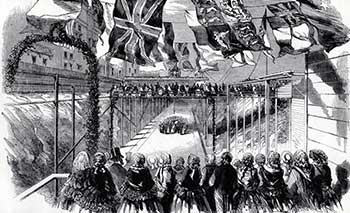

Inauguration of the Dock No: 1

laying of the foundation stone

|

Cottonera has witnessed the birth of Malta’s technological society around the ship repair, building, and servicing industry that developed in Galley Creek. This may have all started in the 1500s – perhaps with the slipway and arsenal in Birgu, which eventually turned out to be one of the best shipyards in the Mediterranean, and even competed with that of Venice.

Even though in the early 1600’s a second shipbuilding yard was built on the Valletta side of the harbour (and eventually destroyed by fire in the 1680s), the galley sheds and the main arsenal (modified, enlarged and rebuilt over the years to meet current exigencies) were all retained in Galley Creek. This also included structures that are associated with the construction, provisioning and administration of the galleys. Furthermore, in the early 1600’s a wooden crane was set up on Sheer Bastion (Macina) to service galleys while another arsenal for the ships-of-the-line was constructed on the Senglea side. Both arsenals were still in use in 1800 when the British came to Malta.

All throughout the Order’s stay, Galley Creek remained as the base of the Hospitaller Squadron. When the squadron was made up of six galleys, they were moored three on each side of the Creek and even the residences of the Galley Captains were shared between Vittoriosa (Marina Grande) and Senglea (Dockyard Terraces). However the General of the Galleys as well as other officials of the Arsenal continued to reside in Vittoriosa. Thus for centuries Galley Creek was the hub where maritime skills were developed and put into practice. Although generally managed by foreigners, this marine industrial and commercial activity must have surely left a positive impact on the socioeconomic standards of the local inhabitants.

Following the Order’s capitulation to Napoleon on the 12th June 1798, the French’s brief stay in Malta left its impact on Cottonera. In fact, while Napoleon immediately relieved Cottonera from the terror of the Inquisition, he also divided Malta into twelve districts with Valletta forming the Municipating of the East – thus depriving Vittoriosa of its former status.

Within three months the French were forced to seek shelter from the disgruntled Maltese in the fortified areas of the island. These included the Cottonera Bastions and Fort Ricasoli where they were to be besieged for the next two years. This deprived Cottonera from its thriving mercantile activity, and its inhabitants from the earnings thereof. Furthermore, to keep control over the Maltese population within the walled towns, the French housed a number of families in small enclaves called Fortini – a move which was socially resented by the local inhabitants. As supplies diminished, the French expelled a large number of citizens from within the Bastions so as to rid themselves from surplus mouths. However in so doing, the French and Maltese therein also unwittingly got rid of all medical personnel at a crucial time when the besieged were being hit by disease. In the end it was a combination of famine and sickness that compelled the French to a negotiated withdrawal on the 5th September 1800.

Under the French blockade, the socioeconomic condition of the people of Cottonera was thus reverted to that of the 1600s, when Cottonera’s main problems were related to employment, transfer, promotion, housing accommodation, requisition orders, building permits, criminality, and disorderliness in the street. At that time the State assisted the socially distressed such as widows, invalids, indigents, and the unemployed by providing them with a modicum of social welfare. The Order provided the service of a state-salaried physician as well as the free distribution of bread, meals, and accommodation to the old, poor and needy. The French however did nothing of the sort.

It is true that such a universal dependence of the inhabitants of Cottonera on the benevolence of the charitable distribution of supplicated favours by a Hospitallier state would have helped to extend the people’s submission to an undisputed magisterial authority. This would have no doubt strengthened and rendered more secure the highly centralised authority of the magistracy. However the absence of such benevolence certainly did nothing to improve the economic stagnation and consequent social misery of the Maltese people.

On the other hand, the heritage of a community is not just made up of majestic buildings and a benevolent approach by its rulers: it also embraces much wider aspects including the characteristics of its community and its way of life. Under the French, Cottonera appears to have lost all. Conversely the British, although in a different manner, appear to have addressed these issues quite satisfactorily.

The arrival of the British, with their massive presence along with their military and naval activities in the area, has undoubtedly contributed significantly towards the improvement of Cottonera’s living standards. During the British era the presence of such a naval fleet in the area, the various regiments billeting in Cottonera, the introduction of new technology, and the need of more skilled workers, all contributed to usher in a new socioeconomic revival for the Region.

Nevertheless the standard of living can only be sustained by rising employment, its type, and eventually the income derived from it. In the case of Cottonera this was significantly influenced by the British Military and Naval activity in the area. Up until the mid-1800s, Vittoriosa was associated with the naval establishment that fostered a tradition of industrial skills. On the other side, Senglea was associated with the mercantile trade and its enterprising class exploited the situation to create wealth while diversifying job opportunities based on a trading economy. Senglea’s grid town plan and more palatial buildings also served to give it a more vibrant social life and cosmopolitan appearance.

However the emergence of the Naval Dockyard in the second half of the 19th Century, while regenerating economic performance, also left its adverse impact on Cottonera’s social way of life. Cottonera, particularly Vittoriosa, was a favoured place of residence for Dockyard workers, and this was reflected in population statistics. By 1921-40 half the dockyard workers resided in Cottonera. However the increase in employment also meant the cannibalisation and fragmentation of the auberges as well as of many artistic houses into smaller housing units to accommodate the increasing number of the working class population. By the mid-1800’s the social situation had deteriorated to such an extent that it is recorded that in Cottonera “everything has a dull, bygone shabby look – no life nor movement are here to be seen – the by-street would not bear investigation, the houses are dilapidated”.

On the other hand, with dockyard workers earning above national average income, the socioeconomic standard for the Cottonera area, although below that of Valletta, rose above that of the villages and of Mdina. Furthermore the presence of thousands of sailors in the area, and of the various regiments in the region particularly around World War I contributed further towards Cottonera’s economic prosperity.

In the meantime, Cospicua had also developed into a residential area for merchants and wealthy Maltese gentry. However amongst the Cottonera localities, Senglea fared best between 1849 and 1939. For long stretches it had the highest middle income group which created wealth and enjoyed a higher social status. This gap had narrowed by 1939 and eventually diminished.

This meant that up until the Second World War, the Dockyard’s development and performance coupled with the military activity in the area had generally improved and consolidated the socioeconomic revival of the Cottonera Region.

A higher income enabled Cottonera’s parents to pay for their children’s education in private schools and thus enable them to receive a higher form of education in secondary and tertiary institutions. In fact, when the British closed its military hospital near St Jacob’s Bastion in 1920, the building was converted into a school – St Edward’s College which opened in 1929 and is still running. A higher literate class enjoyed better chances to compete for available opportunities and enhanced its political influence at a time when the franchise was based on wealth and literacy.

Indeed throughout the last centuries Cottonera has been producing some of Malta’s most prominent personalities. Vittoriosa produced the first and only Maltese Cardinal – Fabrizio Sciberras Testaferrata, Malta’s First Archbishop – Mons Sir Michael Gonzi,and Malta’s first post Second War Prime Minister – Sir Paul Boffa. Senglea produced the first Maltese Bishop of Malta – Ferninando Mattei who was eventually raised to Archbishop of Rhodes on the 30th April 1807. Amongst the Senglean politicians there was George Mitrovich (1794-1885) who was instrumental for the appointment of the 1836 Royal Commission which let to Malta being granted the Freedom of the Press in 1839, and Mons. Ignazio Panzavecchia who was elected Malta’s first Prim Minister under the 1921 Self Government Constitution – a position which because of his ecclesiastical status he had to decline in favour of Joseph Howard. Cospicua also produced another post-war Prime Minister – Domenic Mintoff who served as Prime Minister under four legislations, as well as his successor – Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici and a President of the Republic – Ugo Mifsud Bonnici.

Indeed throughout the last centuries Cottonera had not only generated a significant economic/social development within its Region but has also contributed consistently to Malta’s ecclesiastical and political leadership which has carved Malta’s history and influenced its destiny.